The Federal Reserve reduces interest rates in order to encourage businesses and consumers to borrow more money, adding fuel to the economy. The banks will benefit by the rising demand for loans. But the profit from each loan will be lower, as will the amount the bank makes by investing in short-term debt securities.

Both inflation and interest rates are often cited in macroeconomics. Inflation is a term that refers to the rise in the price of goods and services. The most used source of inflation data is the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which is released on a monthly basis from the Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Interest Rates are the amount charged by a lender to borrowers. In the United States, this rate is based on the federal funds rate set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). In simple terms, this rate is set by the Federal Reserve or the central bank of the US (yes it is a private bank and not a branch of the federal govt). The Fed attempts to manipulate inflation by adjusting this rate, this essentially allows them to expand and contract the money supply.

The US banking system is a fractional reserve system, and in this system interest rates and inflation tend to have an inverse relation.

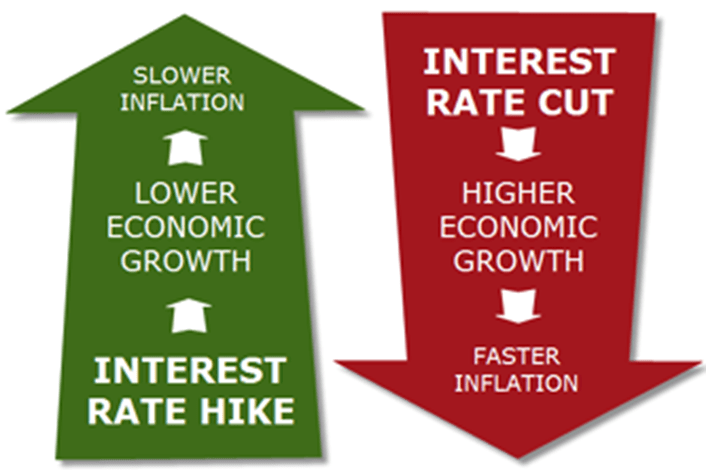

Why is this the case? Well, this is because as interest rates are reduced, consumers tend to borrow more money because with lower interest rates it is cheaper for them to do so. As more money is lent out, the money supply increases and typically expands the economy, due to all that money being spent, however, the increase in the money supply also causes inflation.

Conversely, when interest rates are increased, people tend to save more and spend less as the rate increase allows higher returns for saving accounts. With less money in active circulation being spent on goods and services, it causes the economy to slow down and inflation to decrease. To better understand why this is the case, you need to understand the Fractional Reserve Banking system which we will cover in future articles.

Total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 187,000 in August, and the unemployment rate rose to 3.8 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Employment continued to trend up in health care, leisure and hospitality, social assistance, and construction. Employment in transportation and warehousing declined.

This news release presents statistics from two monthly surveys. The household survey measures labor force status, including unemployment, by demographic characteristics. The establishment survey measures nonfarm employment, hours, and earnings by industry.

Nonfarm payrolls grew by a seasonally adjusted 187,000 for the month, above the Dow Jones estimate for 170,000, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Friday.

Later this month, the world’s top financial and economic policymakers will pow-wow at the Federal Reserve Bank annual meeting in Jackson Hole to determine whether it is time for the Fed to roll back recession-era policies—e.g. a near-zero benchmark interest rate—put in place to support job growth and recovery.

This would be the wrong decision for the communities that are still struggling to recover and the wrong decision for America. Advocates for higher interest rates point to an improving job market as a sign that America has come back from the recession. But many activists, economists, and community groups know that raising interest rates now would stymie the many communities, particularly those of color, that continue to face persistent unemployment, underemployment, and stagnant wages. As the Fed Up campaign, headed by the Center for Popular Democracy, notes in a report released this week, tackling the crisis of employment in this country is a powerful and necessary step toward building an economic recovery that reaches all Americans—and ultimately, toward building a stronger economy for everyone.

The report, “Full Employment for All: The Social and Economic Benefits of Race and Gender Equity in Employment,” shares a new data analysis by PolicyLink and the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE) estimating the boost to the economy that full employment—defined as an unemployment rate of 4 percent for all communities and demographics along with increases in labor force participation — would provide. While overall unemployment is down to 5.3 percent, it is still 9.1 percent for Blacks and 6.8 percent for Latinos. Underemployment and stagnant wages have further driven income inequality and hinder the success of local economies. By keeping interest rates low, the Fed can promote continued job creation that leads to tighter labor markets, higher wages, less discrimination, and better job opportunities —especially within those communities still struggling post-recession.

Lowering unemployment to 4 percent for all gender and racial groups (the rate of overall unemployment in 2000 when the economy was last at full employment) and increasing labor force participation rates would mean that 14.3 million more Americans are employed, 9.3 million fewer would live in poverty, GDP would increase by $1.3 trillion, and the government would receive an additional $261 billion in tax revenue, according to the report.

Full employment would also have an enormous positive impact on racial inequities in income. Currently, only half of workers of color make at least a living wage ($15/hour), compared to 69 percent of white workers, and median household income within communities of color is significantly lower compared to white households. With full employment, Black households would see their incomes rise 13 percent, Latino households would see a 9 percent increase, and Native American households would see a 19 percent increase.

Armed with this data, which was compiled as part of ongoing economic research by PolicyLink and PERE’s National Equity Atlas team, Fed Up will host its own meeting in Jackson Hole, featuring presentations by this team, activists, economists, and community organizers. This meeting, concurrent with the Fed’s, aims to put pressure on the Federal Reserve to acknowledge those communities of color still mired in the recession and take up policies that will bring full employment to all. While Federal Reserve policies are not the only solution to boosting employment among those communities so often left behind, they are a vital and necessary step towards building a stronger, more inclusive American economy.