NEW YORK — The United States and Iranfreed10 people on Monday in a high-stakes prisoner swap that signaled a partial thaw in the icy relations between the longtime adversaries.

Five American citizens held in Iran made a brief stop in the Persian Gulf nation of Qatar before continuing on to the United States. The U.S. government, in exchange, released five Iranians and unblocked the transfer of $6 billion in frozen Iranian oil funds held in South Korea.

The deal, negotiated over several months, marks a major breakthrough for the bitter foes who remain at odds over a range of issues, including the rapid expansion of Tehran’s nuclear program, its ongoing military support for Russia and Iran’s harsh crackdown on internaldissent.

The arrangement took place hours after President Biden and Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi arrived in New York to attend a gathering of world leaders at the U.N. General Assembly. The two leaders are not scheduled to meet.

Who are the U.S. citizens involved in the prisoner swap with Iran?

Biden, in a statement, said that the Americans freed by Iran had endured “years of agony, uncertainty, and suffering.” He thanked U.S. allies for their help in freeing the prisoners and warned all U.S. citizens not to travel to Iran.

He also held an “emotional call” with the families of the Americans, the White House said.

The prisoners’ release comes as a major relief to their families and supporters, many of whom have waited several years for their return from Iran’s notorious Evin Prison. It has also come under harsh criticism from Republicans in Congress opposed to any agreement that involves the unfreezing of Iranian funds. Though under the agreement the money may be used only for the purchase of humanitarian goods, Republicans argue that the administration should have negotiated a deal with terms more favorable to the United States.

Amid the prisoner deal talks, the United States and Iran also have been discussing a possible informal arrangement that would seek to place some limitations on Iran’s nuclear program. U.S. officials have insisted, however, that those talks are unrelated to the prisoner-exchange negotiations.

The U.S. prisoners freed by Iran include Siamak Namazi, an Iranian American who had been behind bars in Tehran for nearly eight years, the longest duration the Islamic republic has jailed any American. Others include Morad Tahbaz, an Iranian American who also holds British citizenship, and Emad Shargi, an American Iranian dual citizen. Each was released from Evin Prison and placed under house arrest last month, an initial step in the deal.

Two other American detainees involved in the swap have not been publicly identified at the request of their families.

“This is a momentous day for the Namazi family who have not been together — all four of them — since early 2015,” Jared Genser, the Namazi family’s lawyer, said in an interview. “Frankly, we never knew this day was actually going to arrive. The family has been through an extraordinary trauma through this very, very long and painful process. There are many challenges that lie ahead.”

The complex deal involved a carefully choreographed process by both Tehran and Washington, according to U.S. officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe the sensitive arrangement.

Around 9 a.m. Eastern time, once Washington secured confirmation that the five Americans were on a Qatari government plane departing Iranian airspace, a senior administration official transmitted a brief statement to reporters indicating they were “wheels up” and safely en route to Doha. Also on board wasEffie Namazi, the mother of Siamak Namazi, and Vida Tahbaz, the wife of Morad Tahbaz. Also onboard was the Swiss ambassador to Tehran, Nadine Olivieri Lozano, who has helped managed dealings between the United States and Iran in the absence of formal diplomatic relations, officials said.

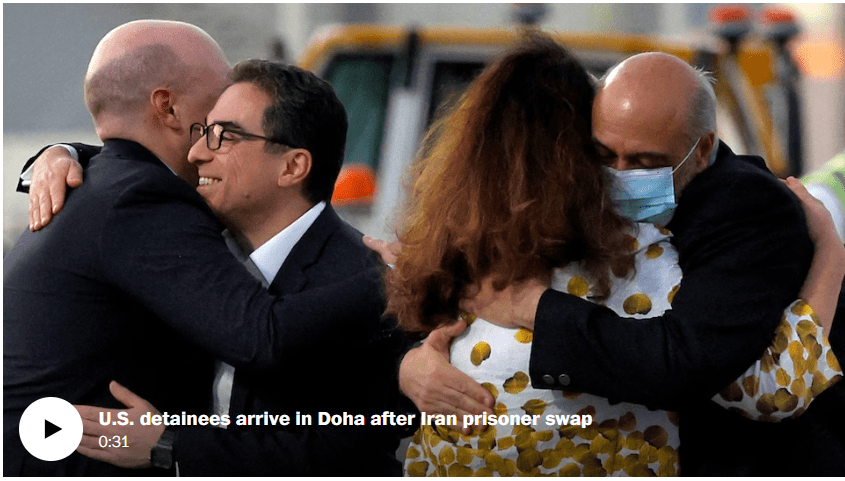

Footage of the Americans’ arrival in Doha, Qatar’s capital, shows Siamak Namazi and Morad Tahbaz emerging from the plane’s cabin and descending to the tarmac, where they were embraced by U.S. officials on hand to greet them. Namazi smiled and waved from the jet’s steps, appearing to savor the moment.

As the Americans left Iran, the United States released five Iranians, some of whom had been charged with crimes but not yet convicted. An Iranian official identified them as Kaveh Afrasiabi, charged with illicit lobbying, Reza Sarhangpour Kafrani, charged with exporting lab gear for Iran’s nuclear program in violation of sanctions, Mehrdad Ansari, serving five years in prison for acquiring military equipment, Kambiz Attar Kashani, who was accused of conspiring to export illegal goods and Amin Hasanzadeh, charged with stealing sensitive planning information.

U.S. officials have describedthem as low-level, nonviolent criminals who do not pose a threat to U.S. national security.

Nasser Kanaani, a spokesman for Iran’s Foreign Ministry, signaled earlier Monday that the deal was proceeding as planned. “Two of the Iranian citizens released in America will return to [Iran], and another person will travel to another country due to the presence of their family, and the other two people will remain in the United States,” Kanaani told reporters, according to Iranian state media.

Meanwhile, a network of private banks and government financial institutions has finalized the transfer of funds to accounts that Iran will have access to under the supervision of the United States.

The $6 billion had been held in South Korea, one of Iran’s largest oil customers, as a result of a waiver issued by the Trump administration in 2018 that permitted Seoul to continue purchasing Iran’s oil. Those funds became stuck in 2019 when the Trump administration tightened sanctions on Iran.

Over the last week, in preparation for the deal to be finalized, those funds were converted from Korean currency to euros before being moved to accounts in Qatar that can only be used for the purchase of non-sanctioned goods, such as food and medicine. U.S. officials say they will continue to have oversight of the money to ensure it is not being used for nefarious purposes.

Raisi, speaking to a small group of journalists in New York, said the unfrozen Iranian oil revenue “belonged to the people of Iran and will be solely spent to address the needs of the people of Iran.”

U.S. officials said Iran can access the money only after the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control issues a document saying the U.S. prisoners have reached their final destination.

Before the prisoner deal, the Biden administration’s rapport with Tehran was marked by deep distrust, largely over the failure to revive a nuclear deal that Biden had vowed to renew when he ran for president. Tehran has refused to talk directly with Washington, requiring third parties to help broker discussions.

The governments of Qatar and Oman played a significant role in facilitating discussions between the two sides over the detainees’ release and hosting the talks, said officials familiar with the matter. Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq also played a role.

The United States’ European allies, which broadly support a revised deal to restrain Tehran’s nuclear program, hope that progress on detainees will help pave the way for more productive nuclear discussions but expectations remain low.

“Iran, through their attitude in past years and particularly recently, has not shown tremendous will to cooperate with the United Nations, with the Vienna Convention, to respect commitments,” French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna told reporters at the United Nations on Monday.

Iran’s nuclear program has expanded significantly following the decision by President Donald Trump to pull the United States out of the 2015 nuclear deal. The accord, forged by the Obama administration, imposed strict limitations on Iran’s program in exchange for sanctions relief.

When asked if the prisoner deal might lead to productive talks on the nuclear front, a senior administration official said, “We do not close the door entirely to diplomacy, but we approach it with principled standards.”

“If we see the opportunity, we will explore it,” the official said.

Susannah George in Dubai and Michael Birnbaum in New York contributed to this report.